Memories of Gingerbread from Colonial Willliamsburg

The crackling of bonfires as they spray firefly-like embers into the chilled night sky, the sound of Christmas carolers strolling cobbled streets in colonial dress, the sweet tartness of hot cider, the smell of firewood tossed into the flame mixed with a hint of fresh cut greenery and hot gingerbread, feet and hands so cold you think they will never feel again, and an all around excitement filling the air. These are some of my fondest sights, sounds, and tastes of Christmas. The Christmas of my childhood, Christmas at Colonial Williamsburg. This was the annual Grand Illumination.

It’s the Christmas of our childhood to which we compare all other Christmases. It’s a high, almost unobtainable, standard that we set for our future selves. Sadly, I fear, none shall ever measure up. For how can anything ever surpass those memories we create in childhood? Will we ever sit anxiously at the top of the stairs wearing our footed pajamas and an excitement almost too intense to bear? Will we every wake from a sleep so innocent that we think we hear hooves on the roof? Will we ever be so precious as to rejoice over a handful of apples, oranges and nuts in the bottom of our stockings? We can never be certain that what we remember is indeed what happened or a precise recording of our past. Visit your old childhood home and although it looks just as it did back then, oddly it is smaller than you remembered, not as far from the school as you remembered. The fence seems a little shorter, the yard needs some TLC.

I go back every now and then, if only in my mind. One day a chill in the air takes me back all those 1500 miles and another it is simply the crunch of leaves beneath my feet. Mostly, a smell caught fleetingly is my quickest ticket “home.” Sadly, I do not get to visit as often as I would like so, I leap at the opportunity to create a piece of this memory or that every now and then.

We were so lucky as kids to live so close to so much early American history. Jamestown, Yorktown, and Williamsburg were our back yard, with Monticello and Mount Vernon just down the street. Not to mention the ocean, the mountains, and the sky line drives around the corner. Our playground was the first permanent English settlement in North America, Jamestown. Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, Powhatan, George Washington, James Madison, James Monroe, Robert E. Lee, Booker T. Washington, Sir Walter Raleigh and Thomas Jefferson were our playmates. We built replicas of wigwams and learned how to candlewick. We learned about moats, tobacco and peanuts. We danced the Virginia Reel. We ran across the same battle fields where General Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington during the American Revolutionary War and climbed over cannons that today still stand watch over the fields. We wore colonial aprons and hats, bought licorice root, nutmeg, and gingerbread. We learned words like encampment and settlement. We visited cobblers, blacksmiths, bakers, glassblowers, candle makers and type setters. We sailed the James River and the Chesapeake Bay. We tasted the salt of the ocean and screamed as the undertow threatened to steal us away. We watched whitecaps grow angry in the wind. We dodged jellyfish and seaweed. We collected shells and fireflies in glass jars. We visited naval bases and air bases. We built sandcastles and buried each other in sand. We went to bed feverishly sun burnt and happy, with salty dampness in our hair and sand in our ears.

Our feet were tired and dusty from the roads we skipped and the fields we ran. Our minds were filled with memories surely to come.

And come they did; sometimes invited and others unexpected, like a friend request from a friend you never thought you would connect with again.

And so it is, that a batch of fresh gingerbread cookies has brought me home again today. And instead of stealing away for a mere moment in my mind, I chose consciously to put pen to paper, or should I say, hands to keyboard. I chose to record this culinary inspired memory as I might record a recipe, in the hopes that I might return to it more often now that it is written. For when it is written, it shall be neither forgotten nor misplaced with time. It can be read and re read. It can be cherished and savored. It can be shared. As I pull the hot tray of gingerbread from my very modern oven, I realize I only went to Williamsburg’s Grand Illumination a few times as a child and that I only ate warm gingerbread pulled from a very colonial oven a few times, yet I remember them both as if it were yesterday.

So what is a Grand Illumination? According to Wikipedia ” A Grand Illumination is an outdoor ceremony involving the simultaneous activation of lights. The most common form of the ceremony involves turning on Christmas lights. One of the older of such community events began at Colonial Williamsburg, the restored Historic District of the former Virginia capital city of Williamsburg in 1935. It is held there each year on the Sunday of the first full weekend in December. Williamsburg’s Grand Illumination, which also involves fireworks, is based loosely on the colonial (and English) tradition of placing lighted candles in the windows of homes and public buildings to celebrate a special event.” It was how Virginia’s first capital officially kicked off the holiday season

So it was here at these gloriously cold Grand Illuminations that I came to smell, taste, see and feel Christmas. I can feel the almost unbearable heat of the bonfire on my face and the simultaneous cold of my feet and hands even now some 30 years later. I can see the glow of a single candle flickering its warm Christmas welcome in each window along the street, I can smell the wood and the greenery. Each doorway is decorated with fresh fruit, usually pineapple, red apples, and fresh greenery. The pineapple, I have come to learn ,was a symbol of hospitality as well as prosperity in Colonial America. Only the most prosperous of colonists could afford a pineapple that came on ships speedily returning from the Caribbean. Often the hostess would give a pineapple to one of her dinner guests. Some hostesses even rented pineapples in order to make a good impression. The following pineapple history can be found on the Welcome Club of Northern Virginia’s website.

The pineapple’s origins are rather fascinating. According to legend, a sea captain returning from the Caribbean islands would signal his safe return from the sea by spearing a pineapple on a fence post outside his home. This became an invitation for friends to visit, share his food and drink, and listen to tales of his voyage. In larger, well-to-do homes, hostesses would go to great lengths to obtain pineapples for her guests, and would keep them hidden in the dining room behind closed doors to heighten visitors’ suspense. Visitors provided with pineapple-topped food displays felt particularly honored by a hostess who obviously spared no expense to ensure her guests’ dining pleasure.

In this manner, the fruit which was the visual keystone of the feast naturally came to symbolize the high spirits of the social events themselves; the image of the pineapple coming to express the sense of welcome, good cheer, human warmth and family affection inherent to such gracious home gatherings.

As the tradition grew, innkeepers used the pineapple symbol on their signs and even bedposts as a sign of welcome. And today, of course, the symbol is used on all manner of items, from glassware to cutlery to hand towels to tableware, to name just a few.

Like the pineapple, apples evoke my memories of Christmas and the Grand Illumination as well. I distinctly remember one particular house or public building that somehow had red apples in place of a few bricks on the outside of the structure. Just recently I found that that building has a name and a interesting reason behind the tradition of the apples.

Here is an article APPLES, PUTLOG HOLES, AND PROVOST MARSHALS; A Christmas Tradition Added to Palmer House History by Jim Bradleyn as it appeared in the CW Journal: Autumn 99

Here is an article APPLES, PUTLOG HOLES, AND PROVOST MARSHALS; A Christmas Tradition Added to Palmer House History by Jim Bradleyn as it appeared in the CW Journal: Autumn 99

The tall brick home at 430 West Duke of Gloucester Street has been called the Kerr House, the Vest Mansion, and the Palmer House in its nearly 250 years, but it may be known best today as the house with the Christmas apples.

Try Christmas the regularly spaced niches in the Flemish-bond brick façade wink with shiny red apples. So adorned, the Palmer House—its official Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area name today—becomes a must-see for December visitors. Who puts those apples way up there, and how, and why?

It takes a hydraulically-operated mobile crane—a “cherry-picker”—to carry the crimson fruit up into the brickwork. A long, folding arm, with an oversized bucket at the end, hoists a landscape department employee into the late autumn air. Two stories above the street, bucket and rider visit each niche. The ritual repeats through the month—as often as required by the weather and the appetites of Williamsburg’s birds. In winter, birds make quick work of ripe apples.

The niches are concessions to the 18th-century realities of building two-story masonry walls. Called putlog holes, they supported the scaffolding as masons laid course upon course of brick. Often, putlog holes were filled with mortar when construction was complete. The putlog holes of the Palmer House stayed open for two decades, until 1779 when mortar filled the blanks, but it wasn’t until 1953 that they were filled with apples.

Harold Sparks, retired Colonial Williamsburg vice president of marketing and merchandising, moved into the Palmer House in 1952, soon after it was restored and the putlog holes were reopened. In an interview just before his death on August 28, Sparks said that he began the apple tradition.

Sparks launched his holiday decorating by hanging a Yule log, strung with long-leaf pine boughs and fruit, next to the front door. Colonial Williamsburg’s architect’s office, responsible for the integrity of Historic Area buildings, reprimanded Sparks for drilling a hole in the brick to insert a hook to support the log.

The next year, Sparks decorated the Palmer House’s front-step iron railings and, borrowing a ladder from the architecture, construction and maintenance department, he put apples in the putlog holes. The ladder wasn’t tall enough to reach the highest holes of the second story—something to remember—but it was a start.

He also discovered that apples left exposed to the elements rot. So, he laquered them, along with the grapes and other fruit he used for decorations, with shellac. A shellacked grape garland was the undoing of a neighborhood rooster. The family across the street kept chickens, including a cock that answered to the name, “Mister Armistead.” One holiday season, Mister Armistead braved the stroll across Duke of Gloucester in search of a snack—and spotted the decorative grapes. Mister Armistead must have been hungry and of one mind, because he overlooked Sparks’s dog, a dalmatian named Duke. Duke had his eye on a snack, too—Mister Armistead. Sparks said his friend Ann Robb “captured on canvas the scene in the street: Duke and Mister Armistead, in a battle to the death—all brought on by my shellacked grapes.”

Putlog holes are what remained after 18th-century bricklayers removed construction scaffolding.

Mildred Layne moved into the house about ten years after Sparks had gone, and no one told her beforehand about the apples. She had been with Colonial Williamsburg since 1937, when she accepted a position as an architecture department secretary. But the architecture department was in New York. Twenty-nine years later, Layne was still in New York, but as administrative assistant to President Carlisle Humelsine, and office supervisor.

Mildred Layne moved into the house about ten years after Sparks had gone, and no one told her beforehand about the apples. She had been with Colonial Williamsburg since 1937, when she accepted a position as an architecture department secretary. But the architecture department was in New York. Twenty-nine years later, Layne was still in New York, but as administrative assistant to President Carlisle Humelsine, and office supervisor.

She came to Virginia late in 1966 as Colonial Williamsburg’s first female administrative officer, the vice president and executive assistant to the president, and moved into the Palmer House on December 23.

Waiting for her family’s belongings to arrive from New York, Layne camped out in the big old place, but, in the spirit of the season, made an effort to decorate the exterior. Early in the morning on Christmas Eve—her second day—a visitor knocked on the door.

“Where are the apples?” the visitor said. “We have been coming here for years, and we have enjoyed seeing the apples every year. This year, we are keeping a promise, and we have brought our grandchildren here to see the apples.”

Mystified, Layne gleaned from the caller what she could about the apples. She stepped outside while the visitor pointed to the putlog holes and described the appearances of Christmases past.

I’ll get the apples,” Layne said to herself, “but how do I get them in the holes?” She dispatched her brother to the market, and Colonial Williamsburg sent a crane around. No sooner had the apples been mounted, but the birds began their Christmas feast, eating them in place or knocking them to the ground. “At some point, the maintenance department inserted short pegs in the holes to secure the apples in place,” Layne says, “but the birds continued to feast on them.”

It was in this very little courtyard that I had my first taste of warm gingerbread pulled from a brick oven and handed me by a colonial baker. In retrospect, I’m not even sure I liked the taste of it back then. I was probably more interested in the chocolate Hostess cupcake packed in my sack lunch. Little did I know that I should be savoring that warm slice of heaven, that I would yearn for it as an adult. Little did I know that we would be moving far far away from this colonial playground of ours and that I would only return to it two times in my adult life.

Decades later, I would excitedly purchase a ticket and take the short stroll to the heart of the colonial town. I would look down every street and peer into every store in the hopes of finding that the bakery still existed all these years later. And with a little luck, a nice map, and a good nose I found a little white gate that marked what I had so anxiously anticipated. We entered from the street and went down a narrow little path that led to a lovely little courtyard. It was then that I knew I had arrived to my destination. I recognized this little place and nothing about it had changed. It was a quite little sanctuary hidden from the street. Groups of visitors could rest their tired feet. I found the screened door that led to my prize and pushed it gently open, almost afraid to go inside and learn that what I sought did not exist. My eyes raced ahead faster than my body. They bounced from wall to wall, counter to counter, searching, imploring, pleading. And there they were, coming out of the oven, little circular mounds of goodness. It was crazy hot outside and stiflingly hotter inside and what I really needed was an ice cold root beer but I had only one goal and it was in sight- gingerbread! I quickly made my purchase and raced back the courtyard. It had been at least twenty years since I had last been to this place and all it took was a little treasure hunt and one bite to bring me right back!

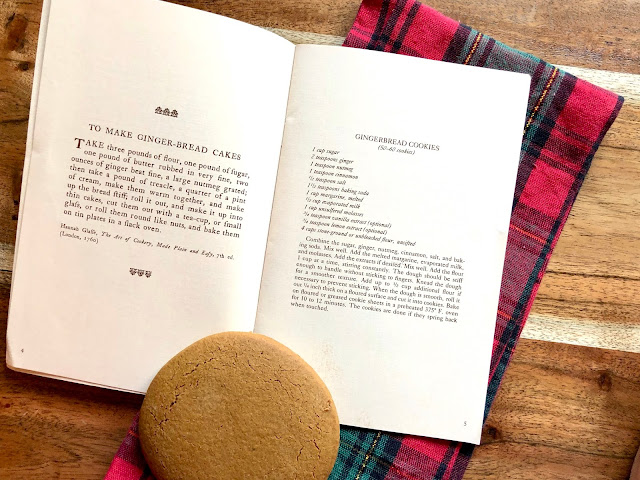

Generations of visitors to Colonial Williamsburg have savored the delectable “ginger-bread cakes” based on Hannah Glasse’s 18th century recipe in “The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy.”

The Raleigh Tavern Bakery sells more than 100,00 ginger cakes annually.

Glasse, Hannah, 1708-1770. Recipes from the Raleigh Tavern Bakery

This is the recipe that I use every year. Nothing beats a warm gingerbread cookie fresh from the oven. We like to prepare them up until the point of baking, freeze, store and bake when desired. That way, we can enjoy the taste, and smell, of warm gingerbread anytime we want.

Comments

Post a Comment